As soon as Nandini suggests meeting at the mangroves, my first thought is to cycle down. The morning I set out though, Goa is 14°; which for Goa, is COLD. I’m pedalling through ear-numbing winds on a foggy morning, but the ride to the mangroves close to Mapusa is surreal nonetheless. The sun is just rising above the horizon by the river; winding slopes pass through brilliantly colourful homes that only make sense in Goa; and to my great relief, we stop for a quick cup of warm tea before we head out to our excursion.

Nandini is the Programme Manager at the Technology for Wildlife Foundation, a Goa-based conservation and research organisation working to ethically utilise tech to help solve conservation’s ever-growing challenges. Nancy, who heads Communications at the foundation accompanies her. They’re warm and greet me with broad smiles, and although I’m meeting them for the first time, I instantly feel like I’d like to see them again.

There is much about these species that is fascinating, as I discover walking along the bund surrounded by mangroves, along a narrow creek of the Mapusa river. Pockets of over sixteen species of mangroves exist across Goa, covering an area of roughly 2,200 hectares. In conditions where a lot of other species would have withered away, these shrubby trees have adapted to almost always being partially submerged in the nutrient-dense, salty swamps they grow in. They’re also capable of absorbing up to four times more carbon from the environment than even the healthiest forests anywhere on the planet. In many tropical flood-prone areas, they form the first line of defence, battling heavy winds and stormy waters.

Walking along the bund surrounded by mangroves, along a narrow creek of the Mapusa river

While mangroves in India would often be equated with the stunning Sunderbans, small and big mangrove forests exist across coastal regions throughout the country, supporting a diversity of living species as homes and means of living. In Goa itself, mangroves influence and are influenced by their complex interactions with other ecosystems, linear infrastructures and communities. Life without mangroves, that are increasingly losing ground to coastal development projects as well as the changing climate, can become very tough very quickly. A part of Tech for Wildlife’s work is to present these complex interconnections, integral associations and immediate threats through strong visual evidence to organisations, individuals, and decision makers that can take the story ahead.

We may have walked no more than 500 metres so far. During the high tide, the steady waters around serve as a fish nursery. A Brahmani kite takes flight, White-cheeked barbets flock a tree, and a kingfisher is perched on a branch further ahead. We’re hopeful of a glimpse of an otter, but it’s not our day. The same path further extends into a khazaan, an agricultural system unique to Goa, built on the indigenous knowledge of some of the earliest tribes.

A Brahminy kite takes flight

In one of their ongoing projects, Tech for Wildlife is helping chart a khazan map of Goa. Nandini recounts with surprise how they were unable to locate consolidated maps for a system that has existed for thousands of years.,. When we talk of preservation and restoration, how do we move ahead if we don’t know where we’re starting from? In these cases, they’re helping establish baseline data using cartography and spatial analysis skills as well as references from existing records and through collaborations with other organisations, to fill in the knowledge and resource gaps.

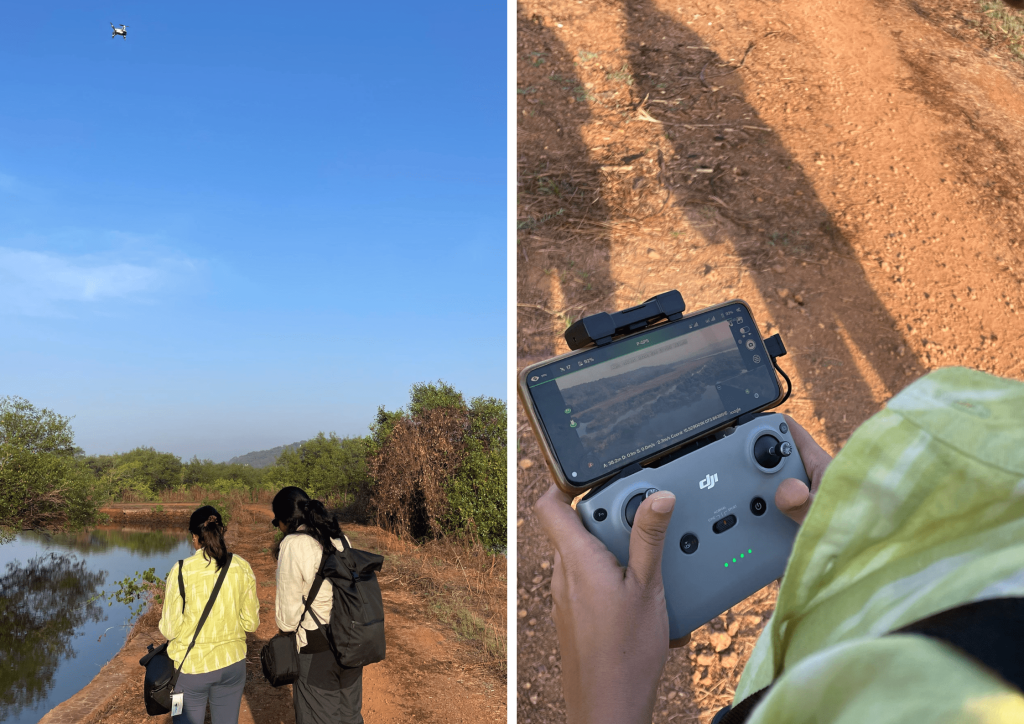

In documenting the marshy landscape that surrounds us, technology plays a different role. These waters pose real challenges, risks and limitations for surveyors, making the task resource and time intensive, while the findings may still not be accurate. Here, the team has been using a combination of drone and satellite imagery, to map and model their presence, and understand more about their extent and their role as carbon sinks. A lot of Tech for Wildlife’s work is experimental, strengthened with each experience as they navigate different challenges with the technology available.

Nandini flies the drone during our visit to the mangroves

The sun is up by the time we return from our walk, and the conversations continue at the roadside shack. Shashank Srinivasan, who founded the organisation in 2017, had an innate inclination towards cartography and robotics. He was also acutely aware of the need to take immediate and innovative action against the rapidly worsening impacts on the environment. These two interests combined in founding the organisation, and Nandini, fresh out of her Masters course, joined the one-person team soon after. “I was drawn to Shashank’s earnestness and his sense of urgency in wanting to do something, and to do it in the way he believed”, she reminisces. After Shashank’s sudden passing in 2023, the team continues to take their work ahead under Nandini’s direction. Tech for Wildlife’s is also a story of people being drawn together by trust, camaraderie and a shared vision.

The Tech For Wildlife Team, Jan 2023.

Technology cannot and should not be looked at as a be-all and end-all solution to climate and environmental concerns, Nandini reiterates. In fact, the more powerful the tool, the more important it becomes to understand its capacity to influence the environment and use it in a way that doesn’t interfere with, harm or otherwise disrupt the natural landscape. While studying the auditory sensitive gharials, for example, in the Gandak river in Bihar, the team had to be doubly cautious of the use of drones.

The organisation’s distinct view of landscapes and habitats, enabled by the use of tech, helps convey ecosystems and climate concerns from a perspective often unavailable to people. While looking at the crystallisations forming on the succulent leaves of mangroves holds its own kind of attraction, looking at the extent and diversity of our landscapes through drone vision hundreds of feet off the ground, opens up a whole new outlook. Their research has been utilised by organisations across the globe; at the same time, their data has played an important role in improving people’s understanding of their own habitats – like their contribution to documenting Goa’s natural landscapes – strengthening people’s sense of belonging and awareness, and encouraging collective action. The endeavour has been to make everything – the successes, losses, learnings, and resources freely accessible for everyone to learn from and adapt. Taking ahead these learnings is the work of artists, communicators, educators, storytellers. The edifice for these stories is built by the team at Tech for Wildlife. (Link: Understanding Mangrove Carbon, Science Gallery, Bangalore)

Micro view of the salt deposits on leaves v/s the aerial views of mangroves in Goa

Even without intending to, I am more attentive to the biodiversity I am surrounded by in the days following this morning. It would take me many more visits to fully grasp how rich and diverse the state is, but I am grateful for the introduction. Couple of days later I’m taking a cab to the Vasco Railway Station. The trip has been both immersive and whirlwind, in ways that I haven’t entirely comprehended. For now, I’m looking out of the cab, hoping to catch final glimpses of Goa to take back home. The breeze is still cool, like it has generously been for most part of this trip.

Along the NH66 Highway, a little ahead of Panjim, I see a stretch of mangroves along the road. These are nothing like the mangroves I saw the other morning though. The lush greens are replaced by a ghostly grey. I was told about this, but it is dismaying to encounter it nonetheless. The visual I carry with me is a humble and unfortunate reminder that ecosystems – resilient, enduring, adaptive- are still not indestructible. Everything, no matter how enduring, will invariably reach a breaking point; my hope and wish is that nothing is pushed to it.

Great post!